Elementary algebra

Elementary algebra is a fundamental and relatively basic form of algebra taught to students who are presumed to have little or no formal knowledge of mathematics beyond arithmetic. The major difference between algebra and arithmetic is the inclusion of variables. While in arithmetic only numbers and their arithmetical operations (such as +, −, ×, ÷) occur, in algebra, one also uses symbols such as x and y, or a and b to denote variables.

Contents

|

Features of algebra

Variables

The purpose of using variables, symbols that denote numbers, is to allow the making of generalizations in mathematics. This is useful because:

- It allows arithmetical equations (and inequalities) to be stated as laws (such as a + b = b + a for all a and b), and thus is the first step to the systematic study of the properties of the real number system.

- It allows reference to numbers which are not known. In the context of a problem, a variable may represent a certain value which is not yet known, but which may be found through the formulation and manipulation of equations.

- It allows the exploration of mathematical relationships between quantities (such as "if you sell x tickets, then your profit will be 3x − 10 dollars").

Expressions

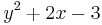

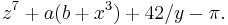

In elementary algebra, an expression may contain numbers, variables and arithmetical operations. These are conventionally written with 'higher-power' terms on the left (see polynomial); a few examples are:

In more advanced algebra, an expression may also include elementary functions.

Operations

Properties of operations

| Operation | Is Written | commutative | associative | identity element | inverse operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addition | a + b | a + b = b + a | (a + b) + c = a + (b + c) | 0, which preserves numbers: a + 0 = a | Subtraction ( - ) |

| Multiplication | a × b or a • b | a × b = b × a | (a × b) × c = a × (b × c) | 1, which preserves numbers: a × 1 = a | Division ( / ) |

| Exponentiation | ab | Not commutative | Not associative | 1, which preserves numbers: a1 = a | Logarithm (Log) |

- The operation of addition...

- has an inverse operation called subtraction: (a + b) − b = a, which is the same as adding a negative number, a − b = a + (−b);

- The operation of multiplication...

- means repeated addition: a × n = a + a +...+ a (n number of times);

- has an inverse operation called division that works for non-zero numbers: (ab)/b = a, which is the same as multiplying by a reciprocal, a/b = a(1/b);

- distributes over addition: (a + b)c = ac + bc;

- is abbreviated by juxtaposition: a × b ≡ ab;

- The operation of exponentiation...

- means repeated multiplication: an = a × a ×...× a (n number of times);

- has an inverse operation, called the logarithm: alogab = b = logaab;

- distributes over multiplication: (ab)c = acbc;

- can be written in terms of n-th roots: am/n ≡ (n√a)m and thus even roots of negative numbers do not exist in the real number system. (See: complex number system)

- has the property: abac = ab + c;

- has the property: (ab)c = abc.

- in general ab ≠ ba and (ab)c ≠ a(bc);

Order of operations

In mathematics it is important that the value of an expression is always computed the same way. Therefore, it is necessary to compute the parts of an expression in a particular order, known as the order of operations. The standard order of operations is expressed in the following chart.

-

-

- parenthesis

- exponents and roots

- multiplication and division

- addition and subtraction

-

A common mnemonic device for remembering this order is PEMDAS. Generally in Elementary Algebra, the use of brackets (often called parentheses) and their simple applications will be taught at most of the schools in the world.

Equations

An equation is the claim that two expressions are equal. Some equations are true for all values of the involved variables (such as a + b = b + a); such equations are called identities. Conditional equations are true for only some values of the involved variables: x2 − 1 = 4. The values of the variables which make the equation true are the solutions of the equation and can be found through equation solving.

Properties of equality

- The relation of equality (=) is...

- reflexive: a = a;

- symmetric: if a = b then b = a;

- transitive: if a = b and b = c then a = c.

- The relation of equality (=) has the property...

- that if a = b and c = d then a + c = b + d and ac = bd;

- that if a = b then a + c = b + c;

- that if two symbols are equal, then one can be substituted for the other.

Properties of inequality

- The relation of inequality (<) has the property...

- of transivity: if a < b and b < c then a < c;

- that if a < b and c < d then a + c < b + d;

- that if a < b and c > 0 then ac < bc;

- that if a < b and c < 0 then bc < ac.

Algebraic examples

The following sections lay out examples of some of the types of alegbraic equations you might encounter.

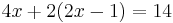

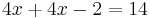

Linear equations in one variable

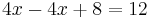

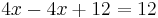

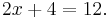

The simplest equations to solve are linear equations that have only one variable. They contain only constant numbers and a single variable without an exponent. For example:

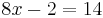

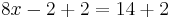

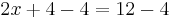

The central technique is add, subtract, multiply, or divide both sides of the equation by the same number in order to isolate the variable on one side of the equation. Once the variable is isolated, the other side of the equation is the value of the variable. For example, by subtracting 4 from both sides in the equation above:

can simplify to:

Dividing both sides by 2:

simplifies to the solution:

The general case,

follows the same procedure to obtain the solution:

Quadratic equations

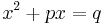

Quadratic equations can be expressed in the form ax2 + bx + c = 0, where a is not zero (if it were zero, then the equation would not be quadratic but linear). Because of this a quadratic equation must contain the term ax2, which is known as the quadratic term. Hence a ≠ 0, and so we may divide by a and rearrange the equation into the standard form

where p = b/a and q = −c/a. Solving this, by a process known as completing the square, leads to the quadratic formula.

Quadratic equations can also be solved using factorization (the reverse process of which is expansion, but for two linear terms is sometimes denoted foiling). As an example of factoring:

Which is the same thing as

It follows from the zero-product property that either x = 2 or x = −5 are the solutions, since precisely one of the factors must be equal to zero. All quadratic equations will have two solutions in the complex number system, but need not have any in the real number system. For example,

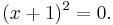

has no real number solution since no real number squared equals −1. Sometimes a quadratic equation has a root of multiplicity 2, such as:

For this equation, −1 is a root of multiplicity 2.

Exponential and logarithmic equations

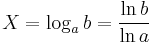

An exponential equation is an equation of the form aX = b for a > 0, which has solution

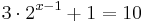

when b > 0. Elementary algebraic techniques are used to rewrite a given equation in the above way before arriving at the solution. For example, if

then, by subtracting 1 from both sides of the equation, and then dividing both sides by 3 we obtain

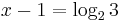

whence

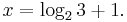

or

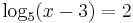

A logarithmic equation is an equation of the form logaX = b for a > 0, which has solution

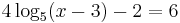

For example, if

then, by adding 2 to both sides of the equation, followed by dividing both sides by 4, we get

whence

from which we obtain

Radical equations

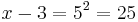

A radical equation is an equation of the form Xm/n = a, for m, n integers, which has solution

if m is odd, and solution

if m is even and a ≥ 0.

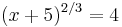

For example, if

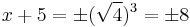

then

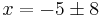

or

.

.

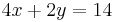

System of linear equations

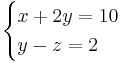

In the case of a system of linear equations, like, for instance, two equations in two variables, it is often possible to find the solutions of both variables that satisfy both equations.

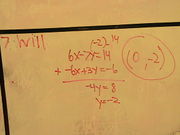

Elimination Method

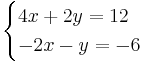

An example of solving a system of linear equations is by using the elimination method:

Multiplying the terms in the second equation by 2:

Adding the two equations together to get:

which simplifies to

Since the fact that x = 2 is known, it is then possible to deduce that y = 3 by either of the original two equations (by using 2 instead of x) The full solution to this problem is then

Note that this is not the only way to solve this specific system; y could have been solved before x.

Second method of finding a solution

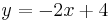

Another way of solving the same system of linear equations is by substitution.

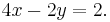

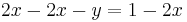

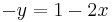

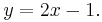

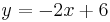

An equivalent for y can be deduced by using one of the two equations. Using the second equation:

Subtracting 2x from each side of the equation:

and multiplying by -1:

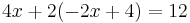

Using this y value in the first equation in the original system:

Adding 2 on each side of the equation:

which simplifies to

Using this value in one of the equations, the same solution as in the previous method is obtained.

Note that this is not the only way to solve this specific system; in this case as well, y could have been solved before x.

Other types of systems of linear equations

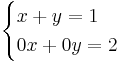

Unsolvable systems

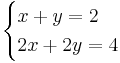

In the above example, it is possible to find a solution. However, there are also systems of equations which do not have a solution. An obvious example would be:

The second equation in the system has no possible solution. Therefore, this system can't be solved. However, not all incompatible systems are recognized at first sight. As an example, the following system is studied:

When trying to solve this (for example, by using the method of substitution above), the second equation, after adding 2x on both sides and multiplying by −1, results in:

And using this value for y in the first equation:

No variables are left, and the equality is not true. This means that the first equation can't provide a solution for the value for y obtained in the second equation.

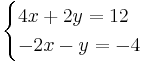

Undetermined systems

There are also systems which have multiple or infinite solutions, in opposition to a system with a unique solution (meaning, two unique values for x and y) For example:

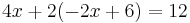

Isolating y in the second equation:

And using this value in the first equation in the system:

The equality is true, but it does not provide a value for x. Indeed, one can easily verify (by just filling in some values of x) that for any x there is a solution as long as y = −2x + 6. There are infinite solutions for this system.

Over- and underdetermined systems

Systems with more variables than the number of linear equations do not have a unique solution. An example of such a system is

Such a system is called underdetermined; when trying to find a solution, one or more variables can only be expressed in relation to the other variables, but cannot be determined numerically. Incidentally, a system with a greater number of equations than variables, in which necessarily some equations are sums or multiples of others, is called overdetermined.

Relation between solvability and multiplicity

Given any system of linear equations, there is a relation between multiplicity and solvability.

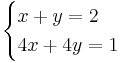

If one equation is a multiple of the other (or, more generally, a sum of multiples of the other equations), then the system of linear equations is undetermined, meaning that the system has infinitely many solutions. Example:

has solutions (x,y) such as (1,1), (0,2), (1.8,0.2), (4,−2), (−3000.75,3002.75), and so on.

When the multiplicity is only partial (meaning that for example, only the left hand sides of the equations are multiples, while the right hand sides are not or not by the same number) then the system is unsolvable. For example, in

the second equation yields that x + y = 1/4 which is in contradiction with the first equation. Such a system is also called inconsistent in the language of linear algebra. When trying to solve a system of linear equations it is generally a good idea to check if one equation is a multiple of the other. If this is precisely so, the solution cannot be uniquely determined. If this is only partially so, the solution does not exist.

This, however, does not mean that the equations must be multiples of each other to have a solution, as shown in the sections above; in other words: multiplicity in a system of linear equations is not a necessary condition for solvability.

See also

References

- Leonhard Euler, Elements of Algebra, 1770. English translation Tarquin Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1-899618-79-8, also online digitized editions [1] 2006, [2] 1822.

- Charles Smith, A Treatise on Algebra, in Cornell University Library Historical Math Monographs.

Footnotes

|

||||||||

![X = \sqrt[m]{a^n} = \left(\sqrt[m]a\right)^n](/I/e311cb67382767a6edecc9fcd76dceb5.png)

![X = \pm \sqrt[m]{a^n} = \pm \left(\sqrt[m]a\right)^n](/I/293c464b10653e28c3585eb43918e19d.png)